Rapid Reports

Six Years of Proposed AI Legislation Across the US States: What’s on Policymakers’ Minds?

Luisa Nazareno, PhD & Nakeina E. Douglas-Glenn, PhD

As artificial intelligence (AI) technologies expand rapidly, public debate has focused on their societal impacts and the need for regulatory oversight. This report offers the first overview of the “what, where, and when” of AI-related legislation introduced in U.S. state legislatures between 2019 and 2024, analyzing key policy trends, priorities, and equity considerations. Although relatively few bills have been enacted, legislative activity has accelerated, reflecting growing political attention to the promises and risks of AI. Most approved bills focus on regulating public or private sector uses of AI, establishing commissions or study groups, and updating education and workforce development programs. While equity is not always central in bill titles or summaries, it surfaces in provisions related to fairness, non-discrimination, transparency, risk assessments, and protections for vulnerable communities, especially in health, employment, and education.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

AI is transformative. Rapid adoption brings both productivity gains and risks like bias, security threats, and job loss.

Regulation lags: Ethics codes are in rapid expansion, but binding regulations remain limited.

In Europe, the EU has approved the most comprehensive AI regulation worldwide. In the Us, regulation efforts at the federal level have been fragmented.

States take the lead: Nearly 900 AI bills proposed (2019–2024), with 142 passed, addressing government and private use, studies, responsible use, and labor impacts.

Equity emerges as a concern: Many bills include fairness, anti-discrimination, privacy, and workforce transition provisions, acknowledging AI’s harms disproportionately affect vulnerable communities.

AI IN PERSPECTIVE

Throughout history, there have been moments when the appearance of technologies has deeply transformed human life. That is the case, for instance, of the steam engine in the 18th century, the telephone and electricity in the 19th century, and, more recently, computers, semiconductors, and the internet in the 20th century. Today, we are once again witnessing a moment of rapid and potentially disruptive change, this time driven by artificial intelligence: computer systems that can perform complex tasks typically thought of as human-specific, such as reasoning, decision-making, and creating.

In many ways, AI is similar to prior technological transformations. However, it is also unique. Whereas past revolutions primarily enhanced mechanical or physical capabilities, AI amplifies cognitive abilities and expands the frontier of what was once thought to be uniquely human. Its transformative potential is such that some have named it a fourth industrial revolution or a second machine age. The pace of AI adoption has also been much faster than before. By early 2024, about 70 percent of organizations worldwide had adopted AI in at least one business function, up from about 20 percent in 2017. Generative AI adoption, in particular, rose sharply from 33 to 65 percent in the past year alone.

AI promises to boost productivity immensely, with some estimates pointing to explosive economic growth of 20-30 percent per year over the next century, far above the average 2 percent since the 1900s. However, accompanying these gains, AI also presents significant risks. These include

threats to national security, such as cyber conflict and autonomous weapons, and social harms caused by biased algorithms, unequal access to technologies, and labor displacement that may affect vulnerable groups. As harms are often not equally distributed, communities already facing systemic disadvantages may be disproportionately impacted.

While it is not possible to predict AI’s impacts perfectly, well-designed public policy can play a role in mitigating negative risks and ensuring that the benefits of AI are equally shared.

REGULATING AI

There is no clear consensus over who should regulate AI or how it should be regulated. In the absence of clear regulations, organizations have increasingly relied on self- or third-party AI certification to signal their commitments to AI ethics. Across public, private, and non-profit sectors, hundreds of ethics codes, principles, frameworks, and guidelines have been published, all aimed at ensuring that the use and development of AI align with values such as fairness, transparency, accountability, and others.

Overall, public and nonprofit documents tend to address a wider range of ethical issues, are more likely to be developed through participatory processes, and are more engaged with legal and regulatory considerations than those produced by the private sector. The private sector, by contrast, tends to lean towards self-regulation rather than formal policy mechanisms. Examples of private sector self-regulation include company-led frameworks developed by companies such as Microsoft, Google, and OpenAI, as well as industry associations’ standards, such as the IEEE Autonomous and Intelligent Systems Standards.

Meanwhile, formal public regulation has followed more slowly. The European Union AI Act, passed in 2021, is the world’s first comprehensive law regulating AI. Acknowledging the complexities of AI systems, this legislation adopted a tiered risk-based framework in which higher-risk applications are subject to stricter requirements. Other AI regulations are being considered by several countries worldwide, but reaching an agreement and making them binding remains uncommon.

In the US, the Executive Order on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy AI (2023) was the first large-scale federal initiative focused on AI governance. It established comprehensive safety and ethical guidelines for AI development and use across federal agencies and the private sector. However, this order was

revoked in January 2025, signaling a shift in the federal priorities from a broad focus on AI safety toward a greater emphasis on national security and promoting free-market innovation.

Debates over AI regulation have also been active in the US Congress. Between 2023 and 2024, over 150 AI-related bills were introduced in the House and the Senate. These bills focused on restricting or clarifying the use of AI, increasing transparency, establishing oversight bodies, safeguarding consumer protections, guiding government adoption, mandating impact assessments, and other related measures. Yet, none of the bills have passed into law, reflecting the contentious nature of these debates.

Meanwhile, several proposals passed into law at the state level, while many others were introduced but ultimately failed. The next section explores the content of these state-level bills.

AI BILLS IN EXPANSION AT THE SUBNATIONAL LEVEL

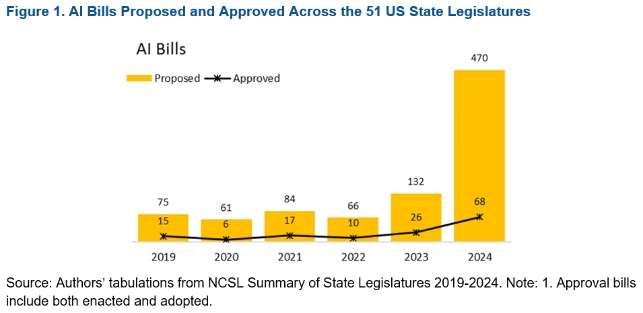

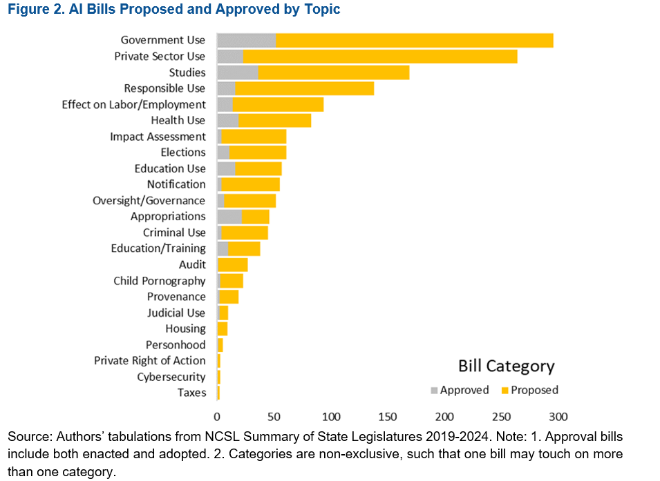

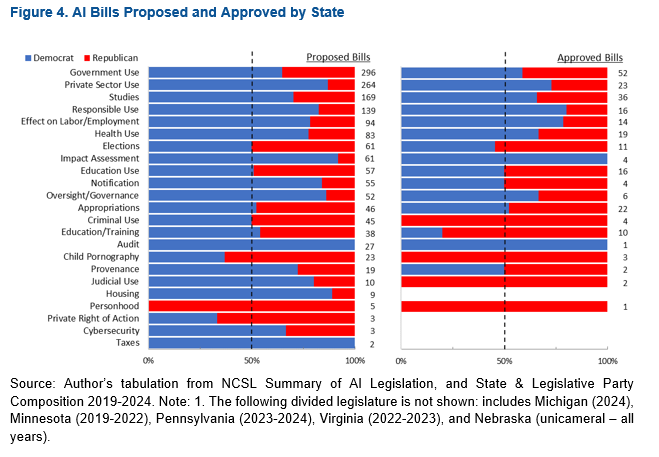

From 2019 to 2024, 888 AI bills have been proposed across the 51 US states, particularly in the past two years, peaking at 132 bills in 2023 and 470 in 2024 (Figure 1). While these bills often target multiple topics simultaneously, most relate to government (296) or private sector (264) use (Figure 2). Studies (legislation requiring a study of AI issues or creating a task force, advisory body, commission, or other regulatory, advisory, or oversight entity) was the third most common topic, appearing in 169 proposed bills.

The next two most frequent topics/categories reflect concerns about the impacts on different groups, thereby having equity as a central theme. In fourth place, responsible use (138) refers to legislation that prohibits the use of AI tools that contribute to algorithmic discrimination, unjustified differential treatment, or impacts disfavoring people based on their characteristics. In fifth, effect on labor/employment (94) relates to AI’s impacts on the workforce, type, quality, and number of jobs.

About 16% (142) of the total proposed bills were approved, with 127 enacted and 15 adopted. The most frequent topics in approved bills were government use (52), studies (36), private sector use (23), and appropriations – or legislation regarding funding for programs or studies (22). The next most frequent topics were AI use in health care or by health care professionals (19), AI use by K-12 and other educational institutions (16), and responsible use (16).

PROVISIONS IN APPROVED BILLS

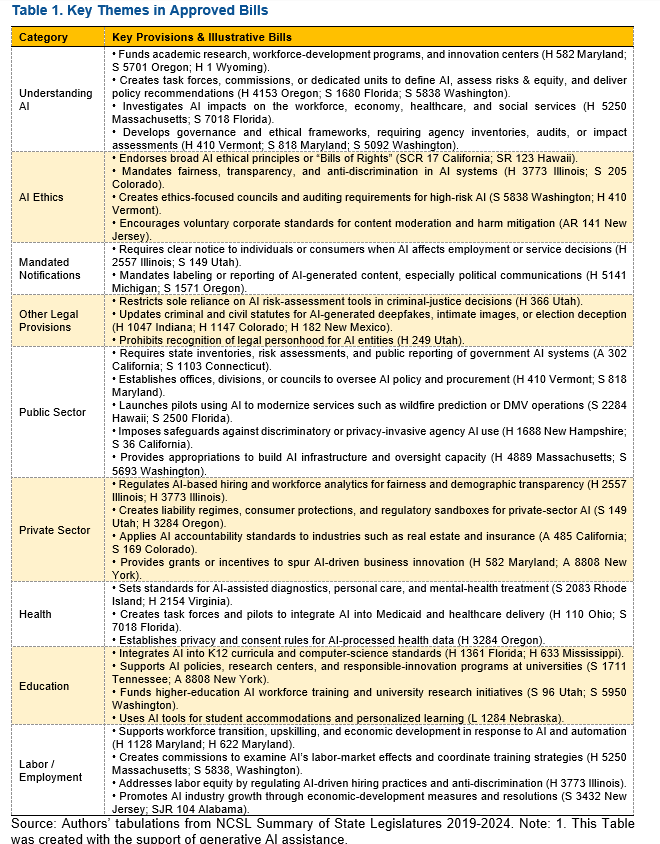

Table 1 summarizes key provisions and examples in approved bills grouped by overarching theme. At this stage, much of the legislators’ attention has focused on better understanding AI and ensuring it is used fairly and accountably. Several measures fund university research, workforce-development programs, and applied-innovation centers (H 582 Maryland; S 5701 Oregon; H 1 Wyoming). Others study AI’s effects on jobs, the broader economy, health care, and social services (H 5250 Massachusetts; S 7018 Florida). Many states have created task forces or commissions to define AI, weigh risks and equity concerns, and craft policy advice (H 4153 Oregon; S 1680 Florida; S 5838 Washington). A few go further, directing agencies to draw up governance frameworks and to inventory or audit every AI system they use (H 410 Vermont; S 818 Maryland; S 5092 Washington).

On the public-sector side, approved bills require state inventories, risk assessments, and public reporting of government AI systems (A 302 California; S 1103 Connecticut); establish offices, divisions, or councils to oversee AI policy and procurement (H 410 Vermont; S 818 Maryland), and launch pilot programs to modernize services such as wildfire prediction, DMV operations, and Medicaid and healthcare delivery (S 2284 Hawaii; S 2500 Florida; H 110 Ohio; S 7018 Florida). Some legislation more directly regulates AI use or alters existing legislation. For instance, restricting sole reliance on AI risk-assessment tools in criminal-justice decisions (H 366 Utah), or updating criminal and civil statutes for AI-generated deepfakes, intimate images, or election deception (H 1047 Indiana; H 1147 Colorado; H 182 New Mexico), or setting standards for AI-assisted diagnostics, personal care, and mental-health treatment (S 2083 Rhode Island; H 2154 Virginia).

Private-sector-oriented legislation concentrates on fairness and accountability. Approved bills regulate AI-based hiring and workforce analytics for fairness and demographic transparency (H 2557 Illinois; H 3773 Illinois), create liability regimes, consumer protections, and regulatory sandboxes for private-sector AI (S 149 Utah; H 3284 Oregon), and apply AI accountability standards to industries such as real estate and insurance (A 485 California; S 169 Colorado). To enhance transparency, some bills require clear notice to individuals or consumers when AI affects employment or service decisions (H 2557 Illinois; S 149 Utah), or mandate labeling or reporting of AI-generated content, especially in political communications (H 5141 Michigan; S 1571 Oregon).

WHERE ARE BILLS BEING PROPOSED AND APPROVED?

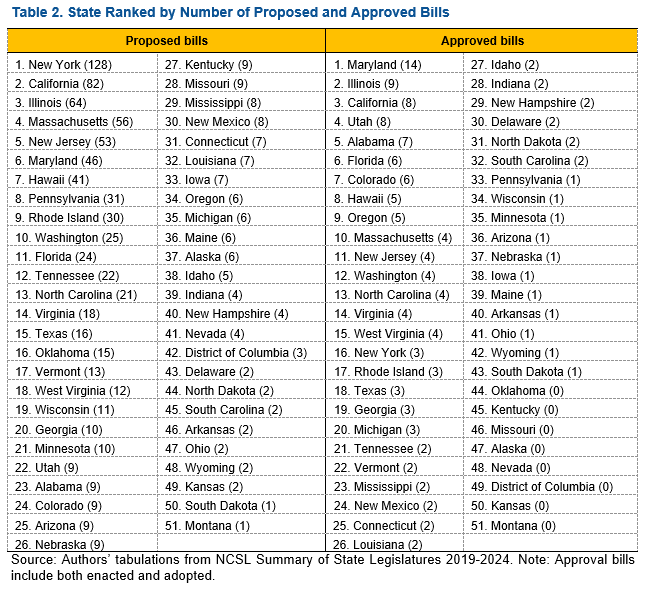

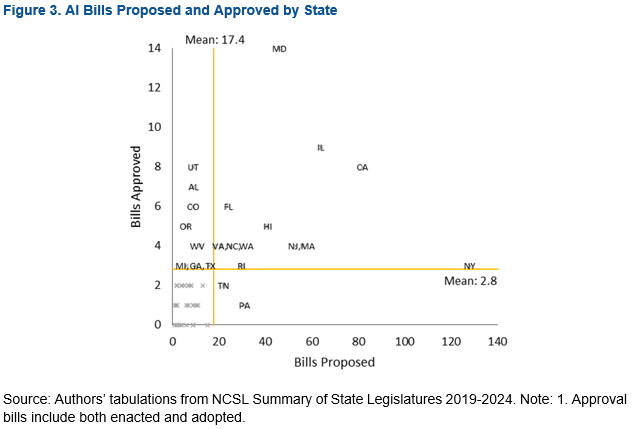

The distribution of proposed and approved bills across the states was uneven (Table 2). New York, California, and Illinois were the top three proponents in the period 2019-2024, respectively, with 128, 82, and 64 bills, much higher than the average state. At the other extreme, the lowest proponents were South Dakota and Montana, with two bills each. Among states with the most approved bills, there were Maryland (14), Illinois (9), California (8), and Utah (8). Meanwhile, the following eight states did not approve any AI bills in the period: Kansas, Kentucky, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, Oklahoma, Alaska, and the District of Columbia. Virginia ranked 14th place both in absolute numbers of proposed (18) and approved (4) bills.

Figure 3 plots states, dividing them into four groups based on whether they are below or above the average in proposed (17.4) and approved (2.8) bills. Maryland, Illinois, and California stand out in the first group: above-average proponents and approvers. Other states in this group include Florida, Hawaii, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Massachusetts, Road Island, Virginia, and Washington. New York is an extreme case, where over 128 bills were proposed but only 3 were approved. The second group – above-average proponents but below-average approvers – includes Tennessee and Pennsylvania.

The third and largest group includes 29 states below-average both in number of bills proposed and approved: Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Vermont, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. Notably, while these states did not rank high among proponents, some successfully approved all their proposed bills. That is the case, for instance, of Delaware, South Carolina, and the Dakotas.

The last group includes eight states that fall below-average proponents and above-average approvers: Alabama, Colorado, Georgia, Michigan, Oregon, Texas, Utah, and West Virginia. Here, Utah stood out by successfully approving 89 percent of its proposed bills.

DEMOCRAT- VERSUS REPUBLICAN-DOMINATED LEGISLATURES

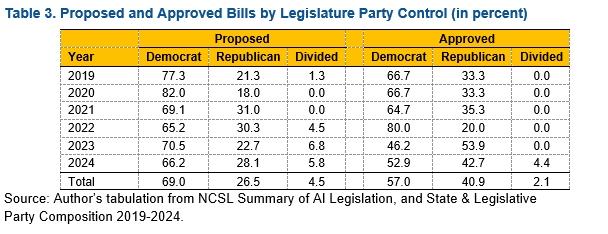

While multiple factors in the legislative process may prevent a bill from being approved, the number of proposed bills is likely a good indicator of how much attention AI has attracted from representatives and in which issue areas. Indeed, legislative assemblies controlled by Democrats and Republicans differ in what is proposed and approved.

Between 2019 and 2024, Republicans controlled about 60 percent of state legislatures and Democrats 40 percent. About 70 percent of all proposed, and 57 percent of the approved, AI bills originated in Democrat-controlled legislatures. However, AI regulation is increasingly appearing in Republican-controlled legislatures as well (Table 3). Furthermore, while Republican legislatures proposed 26 percent of all bills, they approved 41 percent of them. Overall, Democrat-controlled assemblies have been more active in proposing bills, but Republican ones have approved a higher share of what has been proposed.

Among the proposed bills, topics such as elections, education use, appropriations, and criminal use have been equally distributed between Republicans and Democrats (Figure 4). However, Republicans are disproportionately concerned with topics such as child pornography, personhood (whether artificial intelligence can be considered a person), and private right of action. Meanwhile, Democrats’ interests range across various proposed topics, including the ones related to public and private sector use, equity-related areas (e.g., labor market, responsible use, health, and housing), and oversight (e.g., impact assessment, audit, notification, oversight/governance, provenance, and taxes). Though Democrat-controlled areas have proposed more bills to regulate AI use overall, they seem disproportionately concerned with private sector use than Republican-controlled areas, where there is more emphasis on regulating the government.

Approved bills are more evenly distributed, unsurprisingly, as they result from negotiation and voting. Still, it is noteworthy that all impact assessment bills that passed did so in Democratic-dominated legislatures, and all criminal and judicial use bills passed in Republican-dominated ones.

CHALLENGES AND CONSIDERATIONS

AI technologies are in fast expansion and, along with their promised benefits, they also pose risks, as neither benefits nor costs tend to be equally distributed across the population. Regulations can play a critical role in preventing harm and in shaping which kinds of AI can develop freely and which require closer oversight.

While private and nonprofit sectors have moved quickly to propose ethical frameworks and standards, public sector responses have been slower. Fortunately, policymakers are paying attention – arguably at an unseen level. Several bills have been introduced at both the federal and state levels. Although most have not passed, this legislative activity signals an active and growing debate, which is a step in the right direction.

Between 2019 and 2024, most state-level approved bills focus on public or private sector use of AI, or on initiatives to help legislators better understand and monitor AI development. At first glance, equity does not seem to be a primary concern in these bills. However, a closing examination of bill summaries reveals that equity considerations appear quite frequently. Various bills explicitly mandate fairness, anti-discrimination, or demographic transparency in AI systems. Others require periodical risk assessments. Equity also emerges in workforce-transition funding, K-12 curriculum updates, and upskilling programs aimed at preventing technological exclusion. Privacy and consent provision bills, notably in healthcare-related bills, recognize that data-driven harms often fall hardest on already vulnerable communities.

Naturally, the way these provisions translate into practice may vary significantly. This rapid report offered a first look at the “what, where, and when” of state AI legislation, bringing some clarity to the policy landscape. As a next step, we will examine approved bills more closely to assess how equity considerations are reflected in their actual provisions and implementation. We hope this effort will illuminate areas that have already been addressed, as well as the blind spots that must be filled to ensure a more equitable future for AI.